Everything Is a Startup Now

Let’s get this out of the way. Elon Musk, having concluded that the markets for electric cars, orbital rockets, brain computer interfaces, and online arguments were insufficiently disruptive, has identified his next stagnant industry to revolutionize: American democracy. On a Saturday, naturally, via a post on his social media platform X, he announced the formation of the “America Party.” The stated goal, in that particular flavor of grandiosity usually reserved for Series A pitch decks, is to “give you back your freedom”.

One’s immediate reaction might be political. A third party! A challenge to the uniparty! A dramatic fallout with his former ally, President Donald Trump, over a spending bill Musk decried as “debt slavery”. But to view this through a purely political lens is to miss the point entirely. This isn’t a political movement; it’s a business launch. This is the logical endpoint of a world where every problem, from hailing a cab to governing 330 million people, is seen as a total addressable market waiting for a charismatic founder to unlock its value.

The America Party is not a party in the sense that the Federalists or the Whigs were parties. It is, in its structure and ambition, a venture-backed startup. It has a founder with a controlling interest, a lean operational strategy, a disruptive thesis, and a plan for a leveraged buyout of the United States Congress. Is this a political party, a special purpose acquisition company for acquiring legislative influence, or just the world’s most expensive and elaborate form of corporate activism? The fascinating, and frankly terrifying, answer is that it’s all three.

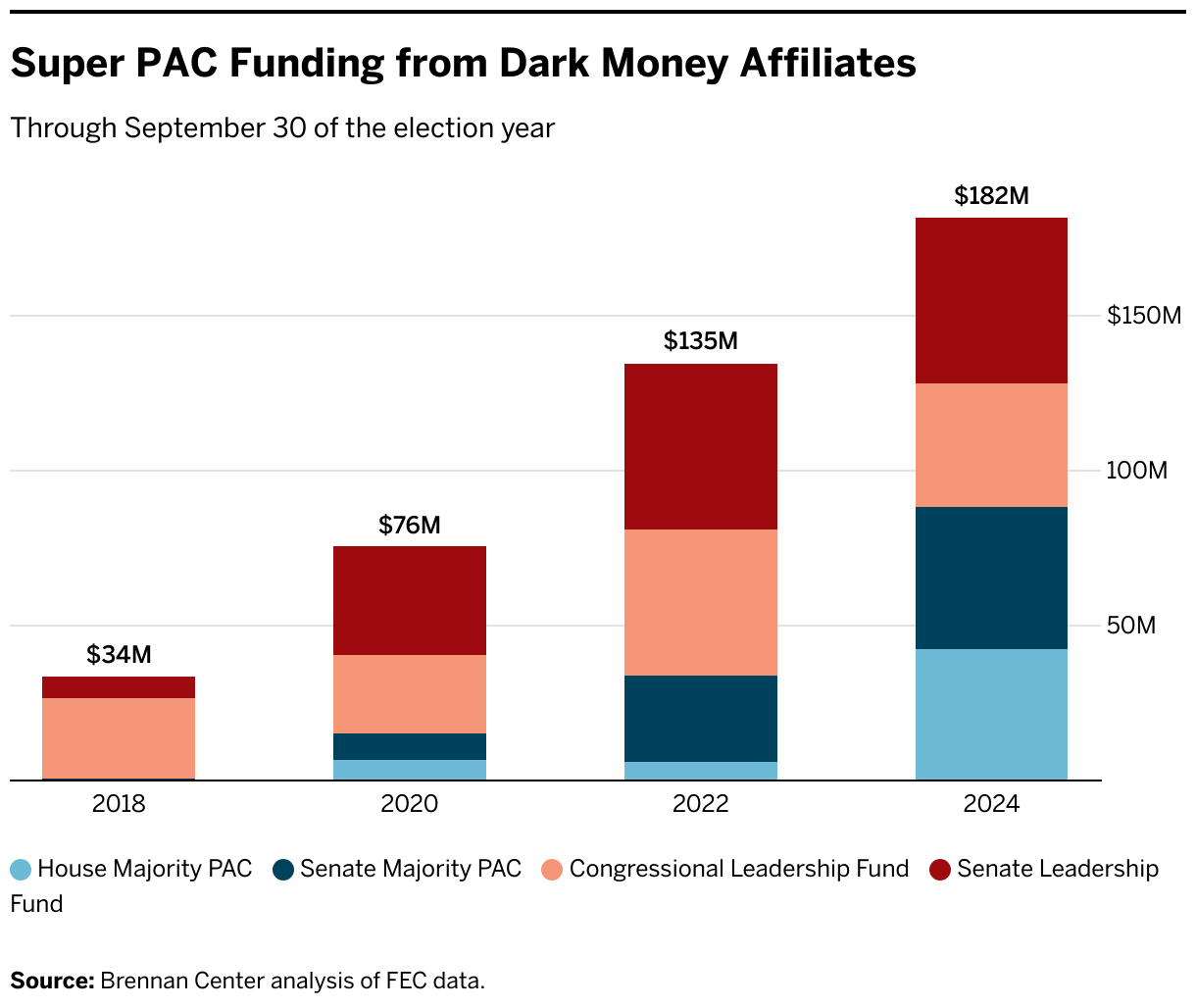

The normalization of this sort of thing is perhaps the most interesting part. A decade ago, a billionaire launching a personal political party after a public feud with a sitting president would have been the stuff of political thrillers. Today, it feels like the next logical step in a well-documented progression. We’ve seen billionaires become kingmakers through Super PACs and dark money. We’ve seen this particular billionaire serve as the head of a federal task force the Department of Government Efficiency, or DOGE where he brandished a chainsaw on stage at CPAC as a prop for his war on bureaucracy. The Overton window of acceptable billionaire political involvement hasn’t just shifted; it has been launched into a geosynchronous orbit aboard a reusable rocket.

So let’s not get bogged down in shock. Let’s treat this announcement as what it is: a term sheet for a new venture. Let’s analyze its strategy, its historical comparables, its risk factors, and what it means for everyone else’s portfolio when the richest person in the world decides to short the government.¹

¹And when we say “short the government,” we don’t mean in the traditional sense of betting against its bonds. We mean in the more literal sense of attempting to acquire a controlling interest in its legislative function in order to, you know, change the terms of service.

Section 1: The Term Sheet for a More Perfect Union

Every startup needs a strategy, a plan to attack the market and achieve an exit. The America Party’s strategy, as outlined by its founder, is a masterclass in financial logic applied to political science. The plan is not to win the presidency—Musk is constitutionally ineligible anyway, a trivial detail that nonetheless shapes the entire venture. Nor is it to win a majority in Congress. The strategy is far more elegant and far more leveraged.

The plan is to “laser-focus on just 2 or 3 Senate seats and 8 to 10 House districts”. In a Congress with razor-thin margins, this small bloc would become the deciding vote on any contentious legislation. This isn’t a grassroots movement; it’s an activist investor play. It’s the political equivalent of buying a 5.1% stake in a public company to get a board seat and force a change in management. You don’t need to own the whole company to control its direction; you just need to own the pivotal shares. This is the leveraged buyout of democracy, aiming for maximum influence with minimum capital outlay. The goal isn’t to be the government; it’s to have the government on a leash held by a board you control.

The Historical Comps

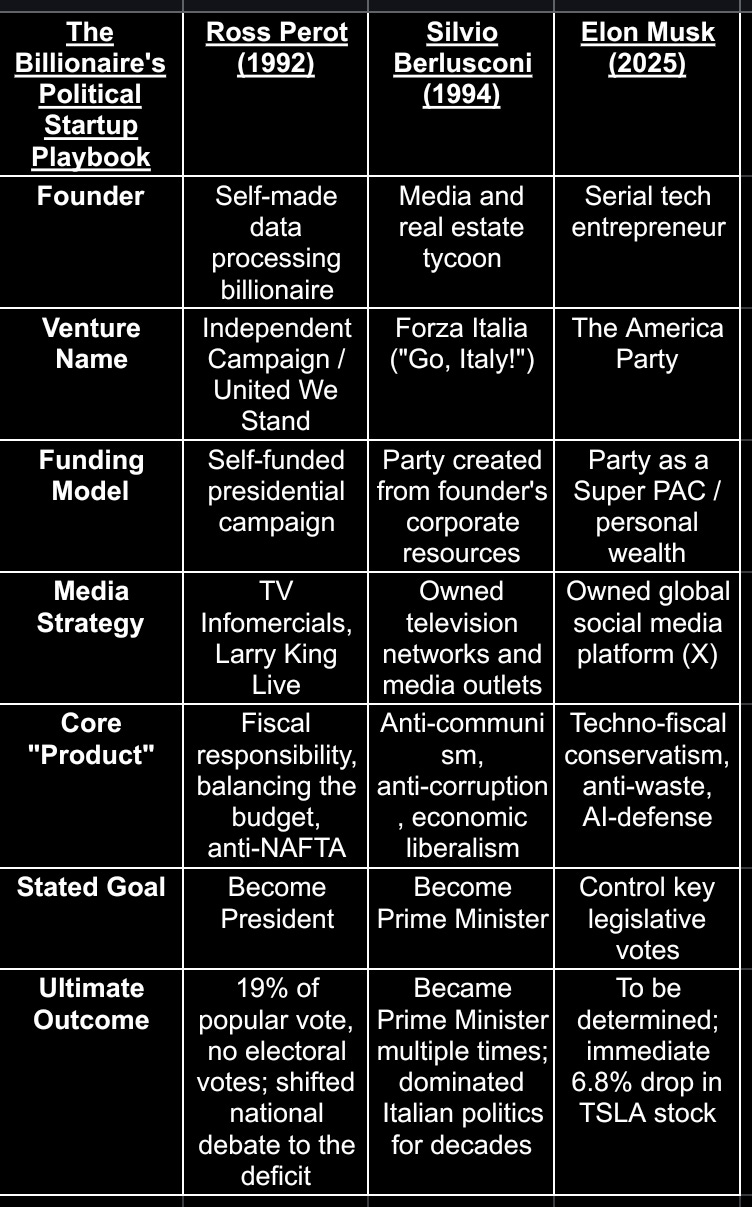

No good pitch is complete without a slide on the comparables, the historical precedents that prove the model. In the world of billionaire political startups, there are two primary comps: Ross Perot and Silvio Berlusconi. Each represents a different vintage of this particular asset class.

Ross Perot’s 1992 campaign was the analog, direct-to-consumer version of this play. A folksy, chart-loving Texas billionaire, Perot bypassed the traditional media gatekeepers of his day by appearing on Larry King Live and buying up 30-minute blocks of primetime television for his famous “infomercials”. He didn’t have a social media platform, so he built his own, one televised lecture at a time. His core message was simple: the political establishment is broken, the budget is a mess, and a no-nonsense businessman needs to get under the hood and “clean out the barn”. His warning about a “giant sucking sound” of jobs going to Mexico under NAFTA was a meme before the internet had a proper word for it. Perot showed that a single, wealthy individual could use mass media to build a national movement from scratch, capturing nearly 19% of the popular vote without winning a single electoral vote, proving that you could have immense influence without actually winning.

If Perot was the direct-to-consumer brand, Silvio Berlusconi was the master of vertical integration. A media mogul who owned Italy’s largest commercial television networks, Berlusconi didn’t need to buy airtime; he was the airtime. When the old Italian political order collapsed in a series of corruption scandals in the early 1990s, he saw a market opportunity. In late 1993, he founded Forza Italia (“Go, Italy!”), a name lifted from a football chant, and staffed it with executives from his own companies. It was less a political party and more a new division of his holding company, Fininvest. By March 1994, just months after its creation, Forza Italia had swept to power, and Berlusconi was Prime Minister. He demonstrated the incredible power of owning the candidate, the party, and the media that covers them all. It was a blitzscaling of political power that would make any venture capitalist weep with joy.

Musk’s America Party is a hybrid of these two models, updated for the digital age. It has the anti-establishment, "let's fix this broken system" rhetoric of Perot, but instead of infomercials, it has a global social media platform with millions of users. It has the corporate-infused structure of Forza Italia, but instead of a media empire, it has a constellation of tech companies and a network of techno-libertarian allies. And most importantly, it has the de-risked, portfolio-based strategy of a modern venture capitalist. Perot and Berlusconi wanted to be the CEO of the country. Musk, constrained by his birthplace and perhaps by his temperament, seems content to be the Chairman of the Board, holding the deciding vote. It’s a more abstract, more financialized, and arguably more durable model of influence.

The Billionaire's Political Startup Playbook

The Risk Factors

Of course, no prospectus is complete without a lengthy and terrifying “Risk Factors” section, and the America Party is no exception. The initial filings with the Federal Election Commission (FEC) have been, to put it mildly, a mess. In the hours after Musk’s announcement, a flurry of entities with names like “America Party” and “DOGE” appeared in the FEC database, listing contacts with untraceable email addresses or, in one case, Tesla’s own CFO. Musk himself had to take to X to disavow one of the filings as fraudulent. This is the political equivalent of your due diligence room containing a bunch of forged documents and a half-eaten pizza. It does not inspire confidence.

Then there are the regulatory hurdles. Gaining ballot access in all 50 states is a "complicated and expensive" legal slog, a patchwork of state laws designed to protect the duopoly. And what, exactly, is the legal status of X in all of this? Is a social media platform owned by the party’s founder an independent media outlet, or is it the largest undeclared, in-kind campaign contribution in American history? The FEC’s rules on coordinated communications are a labyrinth of three-pronged tests about payment, content, and conduct. One can imagine an army of lawyers arguing over whether Musk’s posts about the America Party constitute a “request or suggestion” or “material involvement” in the party’s communications.² This is a legal morass that could make the Delaware Court of Chancery look like a model of clarity and efficiency.

²The fun part is that under FEC rules, a media entity’s own news stories and commentary are generally exempt from being considered contributions. So, is X a media company or a political committee? It seems to be trying very hard to be both, which is usually where the interesting lawsuits start.

Section 2: The CEO as Chief Political Officer

To understand the America Party, you have to understand that it is not an aberration. It is the logical, if extreme, conclusion of a decade-long trend: the rise of the CEO as a political actor. It began innocently enough, with corporate leaders making statements on social issues like LGBTQ rights or gun control, often to placate employees or appeal to a specific customer base. This was framed as “corporate values” or “brand purpose”.

Then came Elon Musk, who has a habit of taking things to their logical conclusion and then pushing them a bit further for fun. His journey from a standard-issue CEO who donates to both parties to a full-blown political operator is a case study in this evolution. The apotheosis of this, before the America Party, was his stint as the head of the Department of Government Efficiency. Here was a sitting CEO of multiple public companies, running a federal task force with a mandate to slash budgets and fire federal workers, all while maintaining his corporate roles. The lines between business and state, between CEO and public servant, had not just blurred; they had been fed into a wood chipper.

Pricing Founder Political Risk

The market, for its part, knows how to react to this. When Musk announced the America Party, Tesla’s stock promptly fell 6.8%. This wasn’t just a random fluctuation; it was the market pricing in a new, exotic, and deeply unhedgeable form of risk. Let’s call it “Founder Political Ambition Risk.”

Investors are used to political risk. They model the effects of elections, trade wars, and regulatory changes. But that’s all macro-level stuff that affects everyone. This is different. This is a specific, idiosyncratic risk tied to the actions of a single individual. It’s one thing when a CEO’s activism on a social issue alienates a segment of the customer base, causing a small and temporary dip in sales. It’s another thing entirely when your CEO enters into a public, high-stakes feud with the President of the United States, who then publicly muses about the CEO’s birth country and threatens to “put Doge on Elon,” a statement that is simultaneously terrifying and nonsensical. This is the kind of risk that keeps corporate governance experts up at night. As one analyst put it, Musk diving deeper into politics is “exactly the opposite direction that Tesla investors/shareholders want him to take”.

Everything Is Securities Fraud

This brings us, as all interesting financial stories eventually do, to the Securities and Exchange Commission. I have a recurring bit called “Everything is Securities Fraud,” which posits that any bad thing a public company does will eventually be litigated as securities fraud, because that’s where the money and the legal hooks are. The America Party is a perfect candidate for this genre.

One must ask, with a perfectly straight face: Is a CEO’s plan to launch a new political party, a party whose express purpose is to antagonize the current administration and its legislative agenda, a material risk that should have been disclosed to shareholders in a Form 8-K filing? The U.S. government is a massive customer for Musk’s companies (SpaceX) and a key regulator for others (Tesla). A public feud that could jeopardize those relationships seems, well, material.

This is, after all, a man with a rich and storied history with the SEC. The 2018 “funding secured” tweet, which led to a $40 million settlement, his removal as Tesla’s chairman, and the installation of a “Twitter sitter” to pre-approve his tweets, set the precedent. The SEC later sued him again, alleging he saved at least $150 million by failing to timely disclose his large stake in Twitter (now X) back in 2022. Given this history, making a market-moving announcement of this magnitude—again, on his own social media platform—feels less like an oversight and more like a deliberate thumb in the eye of securities regulators.

The real beauty of the situation lies in the blurring of fiduciary duty and personal crusade. Why did Musk break with Trump? The proximate cause was the “One Big, Beautiful Bill,” a spending package that, among other things, eliminated green energy credits that directly benefited Tesla’s business. So, is launching a political party to fight this bill a breach of his fiduciary duty to Tesla shareholders—a risky, distracting, ego-driven venture? Or is it the ultimate expression of that duty—using every tool at his disposal, including the creation of a new political force, to protect his company’s financial interests? The business judgment rule gives CEOs enormous latitude to make decisions they believe are in the company’s best interest. Could a CEO plausibly argue that a hostile takeover of Congress is just good business? Musk’s gambit creates a fascinating legal and philosophical paradox, forcing us to ask whether the core business of a modern multinational corporation now includes the direct manipulation of the legislative process as an operational strategy.

Section 3: The Techno-Libertarian Pitch Deck

So what is the America Party’s product? What is it actually selling to voters, or, perhaps more accurately, to its target market of disaffected centrists and fiscal conservatives? The platform, as gleaned from Musk’s posts, is a perfect distillation of the Silicon Valley mindset applied to national governance. It’s Government-as-a-Service (GaaS).

The core features are familiar to anyone who has sat through a tech pitch meeting. The platform calls for reducing the federal deficit and cutting government waste, which is the political equivalent of optimizing cloud server costs and eliminating redundant code. It advocates for deregulation in the science and technology sectors, which is about removing the legacy systems and bureaucratic friction that stifle innovation. And it offers tax incentives for families and manufacturing, which are essentially user acquisition subsidies to encourage desired behavior. This isn’t a political philosophy; it’s a feature set designed to deliver a leaner, more efficient user experience for the citizen-customer.

The Operating System

The ideology underpinning this product is techno-libertarianism, a political philosophy born in the server rooms and boardrooms of Silicon Valley. It’s a worldview that combines radical free-market capitalism with a deep, almost religious faith in technological progress as the solution to all human problems. In this view, the state is not a necessary evil but a buggy, bloated, and obsolete piece of software, an impediment to the glorious, friction-free future that technology promises. The government is the new taxi medallion system, and the techno-libertarians are here with the Uber app to disrupt it.

This ideology has been championed by figures in Musk’s orbit for years, from venture capitalists like Peter Thiel and Marc Andreessen to political figures like Vice President J.D. Vance. The proof-of-concept for this approach was DOGE. Musk’s time as the "Dogefather" of government efficiency was a real-world beta test of this philosophy. The goal was to bring Silicon Valley’s speed and "first principles" thinking to Washington’s sclerotic bureaucracy, to slash budgets, fire "poor performing" employees, and generally run the government like one of his factories. While the initiative claimed to have saved billions, watchdog groups estimated its abrupt cuts may have ultimately cost taxpayers dearly, a classic case of moving fast and breaking things.

The Killer App

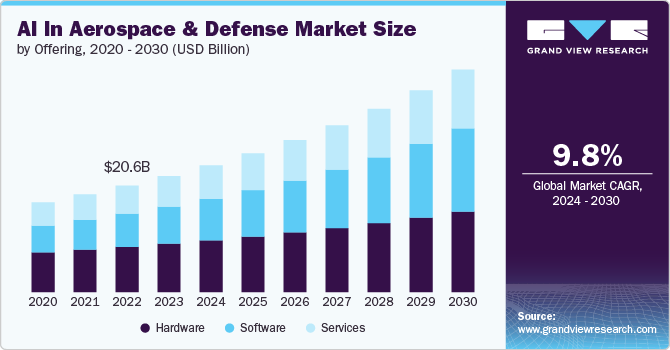

Every successful platform needs a killer app, and for the America Party, that app is artificial intelligence, specifically applied to national defense. The party’s platform explicitly calls for expanding AI-enabled national defense systems. This is not a coincidence. It reflects a massive, ongoing shift in the defense industry, a shift that plays directly to the strengths of the tech world.

The era of traditional defense contractors building fighter jets and aircraft carriers is not over, but it is being supplemented—and in some cases, supplanted—by a new era of software-defined warfare. The new titans of the defense industry are not companies like Lockheed Martin and Northrop Grumman, but tech-native players like Palantir Technologies and Anduril Industries. These companies don’t just build hardware; they build the AI models, data integration platforms, and autonomous systems that are becoming the central nervous system of the modern military.

The government, in this new paradigm, is less a sovereign power commissioning weapons and more a massive enterprise software customer. Palantir’s stock has soared as its Gotham software platform has become deeply embedded in the U.S. government’s data infrastructure, linking everything from IRS and Social Security records to immigration databases in a vast, AI-powered system. This is the quiet backend of the techno-libertarian vision of the state: a government run on algorithms, where decisions are optimized based on massive datasets. The America Party’s defense platform is simply a promise to accelerate this transition, to make the government a better, more lucrative customer for the technologies its founders and allies are building.

This preference for high-tech, centralized solutions also explains the party’s energy policy. The feud with Trump was triggered by cuts to solar and wind subsidies, but Musk has long been an advocate for nuclear power, arguing it is “total madness” to shut down existing plants. This fits the techno-libertarian model: a preference for complex, high-density, technologically sophisticated power sources over distributed, subsidized, and less predictable ones. The ultimate goal is not just to shrink the state, but to capture it and remake it in Silicon Valley’s image. The America Party isn’t trying to abolish the government; it’s trying to win the government contract to become its new operating system provider.

Section 4: So, You Want to Short the Government?

So what does this all mean for you, the investor, sitting at home watching this political drama unfold as if it were a particularly strange episode of a prestige television show? The America Party, as a concept, forces us to reconsider the very nature of political risk and how to navigate it. The advice, naturally, depends on your level of sophistication and your tolerance for absurdity.

For the Everyday Investor

For the retail investor, the primary lesson here is that the world is getting weirder, and your portfolio should be prepared for that. The old rules still apply, but with a new, chaotic twist. A CEO’s political feud can now directly impact the value of a stock you hold in your 401(k). The temptation during periods of high political drama is to make emotionally driven decisions—to sell everything and hide in cash, or to try to time the market based on who you think will win the next election. This is almost always a mistake.

The capital markets, in the long run, are driven by fundamentals like corporate earnings, interest rates, and innovation, not by the political party in power. A well-diversified portfolio, designed to weather market cycles, remains the most prudent strategy. Think of diversification as your best hedge against a world where a billionaire might decide to start a political party on a whim.

That said, one could humorously imagine a "Political Chaos ETF." The fund would go long on defense contractors building AI systems, nuclear power companies, and popcorn manufacturers. It would short the stocks of companies run by CEOs with high social media engagement and a history of public feuds. It would also hold a basket of out-of-the-money put options on the S&P 500, just in case. (This is not investment advice. But if you launch it, I want a cut.)

For the Sophisticated Investor

For the more sophisticated investor, the America Party is not a source of chaos to be hedged; it’s a fascinating case study in a new asset class: political venture capital. The dirty secret of modern American politics is that billionaires have been doing this for years. The Citizens United decision opened the floodgates, allowing unlimited funds to flow into Super PACs and dark money groups. These entities are, for all intents and purposes, the investment vehicles through which the ultra-wealthy seek to generate political alpha. They are used to fund attack ads, support pet causes, and elect friendly candidates who will protect their interests.

The America Party just makes the subtext text. It dispenses with the fiction of "independent expenditure groups" and creates a vertically integrated political machine, wholly owned and operated by its founder. It transforms political influence from a backroom deal into a direct-to-consumer product. This raises a host of fascinating, if unsettling, questions. What is the appropriate risk-adjusted return on a controlling stake in the Senate Banking Committee? Does a political party founder have a fiduciary duty to his donors (the limited partners) and his voters (the customers)?

This is the new frontier of political risk analysis. The old model involved hiring consultants to analyze the political climate in a foreign country before building a factory there. The new model involves becoming a direct participant in the political process of your own country. It transforms political risk from an exogenous variable you manage into an endogenous one you seek to control. Instead of buying political risk insurance, you buy the politicians.

The Re-Pricing of Sovereign Risk

This leads us to the final, and most profound, implication. What if this works? What if the America Party, or a successor modeled on it, becomes a durable force in American politics? This would force a fundamental re-pricing of U.S. sovereign risk.

The entire global financial system is built on the premise that U.S. Treasury bonds are the "risk-free" asset. They are the benchmark against which all other financial assets are priced. This status is not based on a whim; it is based on the unparalleled economic might and, crucially, the political stability of the United States government. It is the belief that the U.S. will always pay its debts because its system of governance is stable, predictable, and governed by the rule of law.

But what if that stability is no longer a given? What if the legislative process can be effectively captured by the highest bidder? What if fiscal policy is dictated not by a national consensus but by the business interests and personal feuds of a handful of tech billionaires? In such a world, is U.S. sovereign debt still risk-free? Or does it need to carry a new risk premium—a "political volatility premium"—to account for the fact that the country is being run like a startup that could pivot or fail at any moment?

The ultimate disruption, it turns out, is not a new app or a new car. It is the idea that a nation-state can be forked like an open-source project, with competing versions vying for market share. The America Party is more than just a billionaire’s vanity project; it is a stress test for the very foundations of democratic capitalism. It collapses the distinction between the market players and the referees, leaving everyone to navigate a world where the rules of the game are themselves for sale. And the most important question for any investor is: what is the correct discount rate for a democracy that has become a venture-backed enterprise?

Maybe we will find out sooner than later!