The Unraveling: A Behavioral Guide to a World on the Brink

The Noise and the Signal

Firstly,

Though we disagree with much of what Charlie Kirk represents, politically driven violence has no place in this world.

Some of the comments i have seen on X are disgraceful. I was in the midst of writing writing about some of the recent global geopolitical drama, and here we are with another.

Condolences to Charlie Kirks family.

Let's get into it

The headlines arrive in a dizzying, disconnected torrent. Russian drones breach the airspace of Poland, a NATO member, testing the alliance’s red lines. A sophisticated attack on critical energy infrastructure in the Persian Gulf temporarily knocks out 5% of the world’s oil supply, sending markets into a brief but violent spasm. The French government, the political anchor of the European project, exists in a state of permanent paralysis, cycling through prime ministers who are powerless to pass a budget in a deadlocked parliament. Across the continent’s economic powerhouses, the United Kingdom and Germany, a 'powderkeg' of social tension ignites into street-level violence, driven by a potent mix of economic pain and cultural grievance. And punctuating the chaos comes the sharp, brutal shock of a political assassination, a violent act that rips through the fabric of civil discourse.

It is tempting to see these events as mere noise the chaotic, random firings of a global system under stress. It is also tempting to seek a grand, unified theory, to connect the dots into a single narrative of conspiracy or a simplistic story of Western decline. Both temptations should be resisted. But is this merely a story of cognitive quirks, or are these predictable, even rational, responses to a system that many feel is rigged against them? While structural economic factors like rising inequality, global supply chain fragility, and institutional decay are undeniably critical, they don't fully explain the character and volatility of our current moment. They set the stage, but our cognitive biases write the script of our chaotic drama.

The truth is both simpler and far more disturbing. These events are not a coordinated plot, nor are they random. They are the predictable, almost logical, outcomes of our flawed human cognitive wiring interacting with a new and unforgiving era of economic and geopolitical shocks. The unifying signal hiding within the noise is not geopolitical, but psychological. Western societies are caught in a dangerous feedback loop, a kind of societal doom spiral driven by the quirks and biases of the human mind. A fundamental, downward shift in our collective economic "reference point" the baseline of expectations against which we measure our well-being has pushed vast populations into a psychological state of loss aversion, making them systematically and predictably prone to risk-seeking behavior. This volatile state is then constantly agitated by high-salience, asymmetric threats that trigger availability cascades and herd behavior, hijacking our perception of risk. All of this is filtered through the distorting, ever-present lens of confirmation bias and social identity, which sorts us into mutually hostile tribes incapable of cooperation. This is not just a series of crises. It is a systemic disequilibrium in our collective decision-making, and understanding it is the first step toward navigating the profound changes that lie ahead.

The Reference Point Has Shifted: Loss Aversion and the Politics of Decline

To understand the current political moment, one must begin not with political science, but with the foundational work of psychologists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky. Their Nobel Prize-winning research on Prospect Theory revealed a profound truth about human decision-making: we do not evaluate outcomes in absolute terms, but as gains and losses relative to a neutral reference point. And crucially, we are not symmetrical in our response. The principle of loss aversion demonstrates that the psychological pain of losing a sum of money is roughly twice as powerful as the pleasure of gaining the exact same amount.

This simple asymmetry has revolutionary implications. When we are operating in a domain of perceived gains when things are going well and we expect them to get better we tend to be risk-averse, preferring a sure thing over a gamble. But when we are in a domain of perceived losses when we feel we are falling behind our reference point our behavior flips. We become risk-seeking, willing to take a dangerous gamble to avoid a certain, painful loss.

For most of the post-World War II era, the implicit reference point for the citizens of Western democracies was one of steady, incremental progress. Each generation expected to be better off than the last. That reference point has been shattered. The new baseline for millions is stagnation, insecurity, or outright decline. As one woman in the UK put it, “Money is just a constant worry and I feel like it's infecting everything”. This has pushed entire societies into the domain of losses.

Nowhere is this dynamic clearer than in France. The nation’s political system is gridlocked not because of a particular leader’s failings, but because of an intractable behavioral dilemma. The state is burdened by a national debt running at 114% of GDP and a budget deficit of 5.8%, nearly double the Eurozone limit. The rational, technocratic solution is austerity. But for the French public, austerity is not an abstract concept; it is a certain, painful loss. As one hospital neurologist protesting in Paris explained, “Public services are failing, the quality of care in hospitals is getting worse... Years of cuts to the health sector means doctors suffer, patients suffer”. Faced with this certain loss, the population becomes risk-seeking. They prefer the high-stakes gamble of political chaos ousting one prime minister after another, supporting mass protests under slogans like "Block Everything" to the guaranteed pain of budget cuts. This is not a failure of the political system; it is the system functioning exactly as Prospect Theory would predict. The chronic instability is a feature, not a bug, of a society making decisions under the shadow of loss aversion. It is a state of rational irrationality.

This same psychological mechanism is fueling the rising unrest across Europe. In the United Kingdom, the drivers are explicit: the crushing cost of living, the visible decay of public services, and widening inequality. In Germany, it is the post-Ukraine cost-of-living crisis, falling real wages, and a sluggish economy that has lost its global edge. These are not future anxieties; they are tangible, daily losses measured against the recent past. They create the deep-seated "grievances" that scholars identify as the primary fuel for civil unrest.

When an entire populace shifts into a risk-seeking mentality, the political calculus changes. Mainstream political platforms that offer painful but prudent trade-offs become electoral poison. This creates a vacuum that is eagerly filled by radical alternatives promising to overturn the game board entirely, even if the odds of success are slim. The steady rise of Marine Le Pen’s National Rally in France and the emergence of new "left-nationalist" challengers in Germany, like the Bündnis Sahra Wagenknecht , are not political anomalies. They are the predictable products of societies that feel they have more to gain from a risky gamble than they have to lose by sticking with a system that delivers certain pain.

The Availability Cascade: How Asymmetric Threats Hijack Our Perception of Risk

The human brain is a poor statistician. To navigate a complex world, it relies on mental shortcuts, or heuristics. One of the most powerful is the availability heuristic: we judge the probability of an event not by statistical data, but by the ease with which examples come to mind. Events that are recent, vivid, emotionally charged, or heavily reported are massively overweighted in our risk calculations. This cognitive quirk is the engine of information cascades and herd behavior, where an initial, highly visible signal can trigger a self-reinforcing loop of public belief and action, often with little connection to underlying reality.

Our modern threat environment seems almost perfectly designed to exploit this vulnerability. Consider the drone incursion over Poland. In purely military terms, a few unmanned aerial vehicles crossing a border is a minor incident. But its psychological impact is enormous. The event is visual, menacing, and easily understood. It makes the abstract threat of a wider war with Russia feel immediate and terrifyingly plausible. It is a perfect availability trigger.

Similarly, a successful attack on a single piece of critical infrastructure, like the 2019 strike on Saudi Arabia’s Abqaiq and Khurais facilities, can have an economic and psychological impact far exceeding its physical damage. That attack, conducted with drones and missiles, temporarily removed 5.7 million barrels per day of oil from the market. The result was an immediate 19% spike in Brent crude futures at market open—the largest single-day price jump in decades. This was a classic herd-driven market overreaction, a global information cascade triggered by a single, highly available event that exposed the fragility of the entire system.

The ultimate availability trigger, however, is political violence. The assassination of a public figure, like the murder of British MP Jo Cox or the shooting of U.S. Congresswoman Gabby Giffords, is a singular, horrifying event that instantly dominates the global information ecosystem. Such acts make political violence, which is statistically rare in stable democracies, feel like an omnipresent threat. They can paralyze political discourse, justify vast and costly security expansions that change the nature of democratic interaction, and provide potent ammunition for partisan blame-casting.

This dynamic has created a new form of asymmetric conflict that is best understood as behavioral economic warfare. The strategic goal is no longer just to destroy military assets but to impose maximum psychological and economic costs on an adversary for minimal investment. By engineering a high-salience event that triggers an availability cascade, a relatively weak actor can induce market panic, sow social division, and force a disproportionate and economically ruinous defensive response. The target is not the enemy’s army, but the cognitive biases of its population. The proliferation of cheap, effective technologies like drones and the tools of cyber warfare has effectively democratized the ability to manipulate the collective psychology of entire nations. This is not merely a change in military tactics; it represents a fundamental and dangerous shift in the stability of the global system. We have entered an era where psychological disruption is a primary strategic objective, and our own minds are the main battlefield.

The Great Sorting: Confirmation Bias and the Partisan Brain

The economic anxiety born of loss aversion and the perceptual distortions created by the availability heuristic are potent forces on their own. But they become truly explosive when poured into the crucible of modern political polarization. The final key to understanding our current unraveling lies in two intertwined behavioral concepts: confirmation bias and social identity theory.

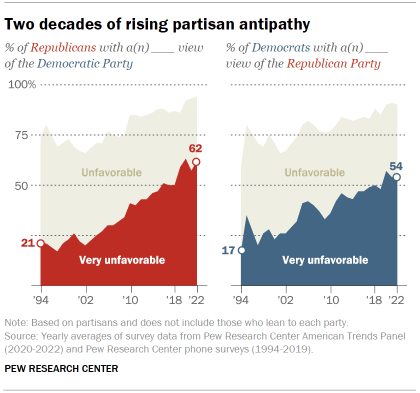

affective polarization chart US ANES

Confirmation bias is our deep-seated tendency to seek out, favor, and interpret information in a way that confirms our preexisting beliefs, while dismissing evidence that contradicts them. This is not a moral failing but a cognitive default. It is closely linked to social identity theory, which posits that a significant part of our self-concept who we believe we are is derived from our membership in social groups. In times of stress and uncertainty, our primary psychological motivation often shifts from a dispassionate search for objective truth to a fervent defense of our group’s identity and its core narratives. This process fuels affective polarization: we don't just disagree with the other side’s policies; we come to actively dislike, distrust, and feel contempt for its members.

The Unraveling: A Behavioral Guide to a World on the Brink

The Noise and the Signal

The headlines arrive in a dizzying, disconnected torrent. Russian drones breach the airspace of Poland, a NATO member, testing the alliance’s red lines. A sophisticated attack on critical energy infrastructure in the Persian Gulf temporarily knocks out 5% of the world’s oil supply, sending markets into a brief but violent spasm. The French government, the political anchor of the European project, exists in a state of permanent paralysis, cycling through prime ministers who are powerless to pass a budget in a deadlocked parliament. Across the continent’s economic powerhouses, the United Kingdom and Germany, a 'powderkeg' of social tension ignites into street-level violence, driven by a potent mix of economic pain and cultural grievance. And punctuating the chaos comes the sharp, brutal shock of a political assassination, a violent act that rips through the fabric of civil discourse.

It is tempting to see these events as mere noise—the chaotic, random firings of a global system under stress. It is also tempting to seek a grand, unified theory, to connect the dots into a single narrative of conspiracy or a simplistic story of Western decline. Both temptations should be resisted. But is this merely a story of cognitive quirks, or are these predictable, even rational, responses to a system that many feel is rigged against them? While structural economic factors—like rising inequality, global supply chain fragility, and institutional decay—are undeniably critical, they don't fully explain the character and volatility of our current moment. They set the stage, but our cognitive biases write the script of our chaotic drama.

The truth is both simpler and far more disturbing. These events are not a coordinated plot, nor are they random. They are the predictable, almost logical, outcomes of our flawed human cognitive wiring interacting with a new and unforgiving era of economic and geopolitical shocks. The unifying signal hiding within the noise is not geopolitical, but psychological. Western societies are caught in a dangerous feedback loop, a kind of societal doom spiral driven by the quirks and biases of the human mind. A fundamental, downward shift in our collective economic "reference point"—the baseline of expectations against which we measure our well-being—has pushed vast populations into a psychological state of loss aversion, making them systematically and predictably prone to risk-seeking behavior. This volatile state is then constantly agitated by high-salience, asymmetric threats that trigger availability cascades and herd behavior, hijacking our perception of risk. All of this is filtered through the distorting, ever-present lens of confirmation bias and social identity, which sorts us into mutually hostile tribes incapable of cooperation. This is not just a series of l

Plausible Scenarios and Pathways: Navigating the Disequilibrium

The global system, driven by these powerful behavioral forces, is in a state of profound disequilibrium. It is unstable and cannot remain in its current state indefinitely. Forecasting the precise future is a fool’s errand, but it is possible to analyze the plausibility of the different pathways ahead. Like a complex system, our interconnected world will eventually settle into a new, more stable state. The critical question is which one.

The interaction of systemic loss aversion, vulnerability to availability cascades, and entrenched political polarization suggests four primary potential futures.

Pathway 1: The Low-Level Trap (High Likelihood)

Description: A persistent state of political gridlock, low economic growth, and recurring social unrest. The system doesn't collapse but remains chronically dysfunctional.

Primary Behavioral Drivers: Loss Aversion (prevents necessary but painful reforms); Confirmation Bias (entrenches political tribes, ensuring paralysis).

Key Indicators to Watch: Continued hung parliaments; recurring budget crises; persistent, low-grade protests; stagnant real wages.

Analysis: This scenario is analogous to the "low-level equilibrium traps" described in development economics, where poor countries remain poor because the incentives for investment and reform are absent. In this future, Western societies remain stuck. The self-reinforcing feedback loop between economic grievance and political polarization proves too strong to break. Loss aversion makes electorates unwilling to accept the short-term pain of necessary fiscal or structural reforms. Confirmation bias and affective polarization ensure that political tribes remain locked in a zero-sum conflict, leading to permanent gridlock. The result is a future of stagnant growth, decaying public services, and recurring but contained outbreaks of social unrest. The system does not collapse, but it festers. This is the most probable future because it requires no major external shock; it is simply the extrapolation of current trends.

Pathway 2: The Shock and Realignment (Moderate Likelihood)

Description: A major crisis (e.g., a wider war, a financial collapse, a severe climate event) shatters the existing reference points and political identities, forcing a fundamental re-sorting.

Primary Behavioral Drivers: Availability Heuristic (the shock is so large it overrides prior biases); Herd Behavior (a rapid cascade toward a new consensus or chaotic collapse).

Key Indicators to Watch: A direct military confrontation between major powers; a Lehman-style financial event; a sudden spike in political assassinations.

Analysis: This is the high-volatility scenario. The current equilibrium is shattered by a crisis so large and so undeniable that it acts as a "critical juncture," resetting reference points and scrambling political identities. A direct military confrontation between NATO and Russia, a global financial crisis on the scale of 2008 or greater, or a series of catastrophic climate-related events could serve as such a shock. The availability of this new, overwhelming threat would be so powerful that it could momentarily override entrenched partisan biases, forcing a rapid, herd-like cascade toward a new consensus. This outcome is not necessarily positive; the realignment could be toward a more cooperative, resilient society (as seen after World War II) or toward authoritarianism and systemic collapse. The outcome is uncertain, but the probability of such a shock occurring in our fragile and interconnected world is significant and rising.

Pathway 3: The Adaptive Muddle (Emerging Likelihood)

Description: Systemic dysfunction persists, but individuals and communities adapt by building resilient local and digital networks, creating parallel systems to cope with state failure.

Primary Behavioral Drivers: Bounded Rationality (accepting state limits); Social Identity (re-forms around smaller, more effective local or digital communities).

Key Indicators to Watch: Growth of mutual aid networks; rise of local currencies or barter systems; increased investment in community-level resilience (e.g., local food, energy).

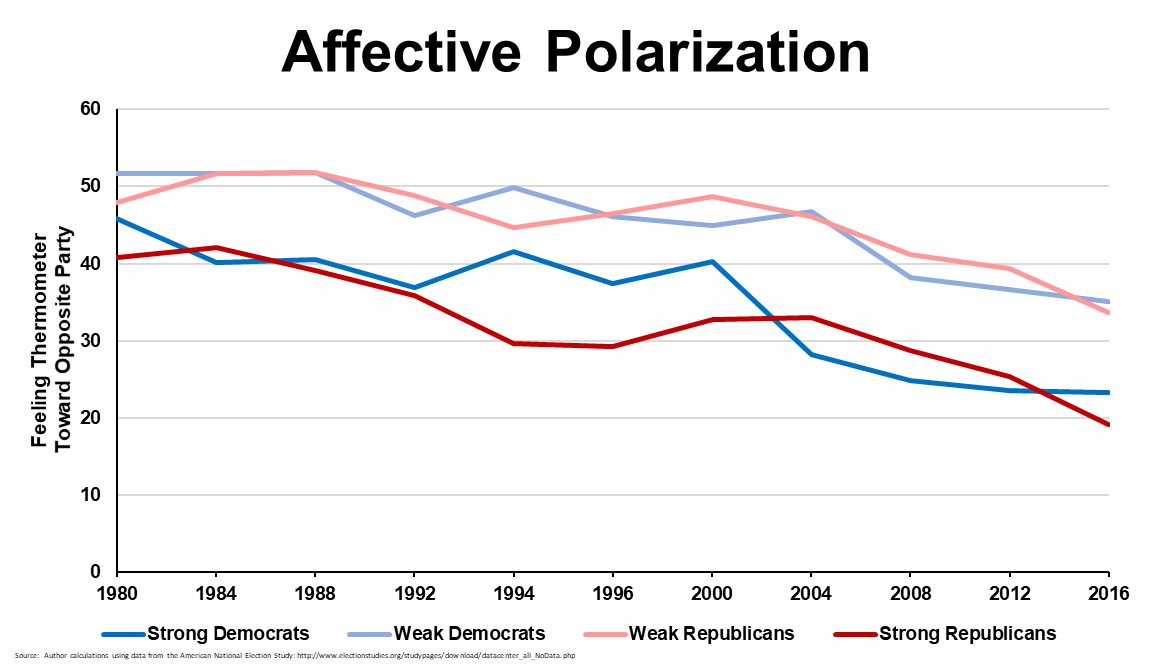

Pew Research partisan animosity chart

Analysis: This scenario represents a more complex, bottom-up response to systemic failure. It posits that as faith in the efficacy of national and international institutions wanes, citizens will stop waiting for top-down solutions. Instead, they will adapt by building more resilient local and digital communities to insulate themselves from the chronic dysfunction of the "Low-Level Trap". This could manifest as a rise in mutual aid networks, local food and energy systems, and digital communities built around shared values rather than national identity. It is not a solution to the larger problems but an adaptation to them—a form of societal self-preservation that re-routes social capital away from dysfunctional national politics and toward more effective, smaller-scale governance. This pathway represents a fundamental shift in how and where citizens find their security and sense of belonging.

Pathway 4: The Rational Breakthrough (Low Likelihood)

Description: Institutions and policymakers find just enough "nudges" and partial solutions to de-escalate crises and mitigate the worst effects of the behavioral feedback loops.

Primary Behavioral Drivers: Bounded Rationality (acknowledging cognitive limits and designing smarter policies); Present Bias Mitigation (creating commitment devices for long-term fiscal health).

Key Indicators to Watch: Successful bipartisan compromises on major issues; decline in affective polarization metrics; effective international crisis management.

Analysis: This is the optimistic, technocratic scenario. It rests on the hope that policymakers and institutions can become sophisticated applied behavioral economists. By understanding the cognitive biases that drive public behavior, they could, in theory, use the principles of choice architecture and "nudging" to design policies that de-escalate crises and mitigate the worst effects of the feedback loops. This might involve framing policies to avoid triggering loss aversion or creating commitment devices to overcome political present bias. This pathway is assigned a low probability because the forces of affective polarization and risk-seeking behavior are currently so powerful that they seem to overwhelm attempts at rational, evidence-based policy design. It remains a possibility, but it is a hope, not a probability.

Understanding these biases does not grant us immunity from them. We are all susceptible to the pull of the tribe, the sting of loss, and the terror of the available threat. The challenge, then, is not to achieve a state of perfect rationality, but to cultivate a habit of self-awareness—to ask not only what we believe, but why we believe it. In a world on the brink, this cognitive vigilance may be the only compass we have. The unraveling, for now, continues.

Excellent analysis. But you miss immigration as a key (the primary?) driver of political destabilisation in Europe.